Many years ago, an owner of 1711 New Hampshire Avenue, NW

approached us with a history mystery; she had found several steamer trunks with

the name ‘Grant’ painted on them, and wondered if it were at all possible they

could have once belonged to the Ulysses Grant family. We not only found the connection, but found a

Russian Princess to boot.

The house had been built in 1911-1912 at a cost of $25,000 by

Franklin Sanner, who was developing other large properties close by as

speculative development.

It was designed

by Albert Beers.

Owner Sanner sold the residence to Ida Honoré Grant on

September 17, 1912, as recorded Liber 3547, Folio 366. She listed herself in

the 1915 City Directory as the widow of Frederick Dent Grant, the eldest son of

famed Civil War General and President Ulysses S. Grant, and was from a wealthy

and prominent Chicago family. She was listed as the sole resident at the address

in the 1913 City Directory. The couple is pictured at right.

As the son of Ulysses S. and Julia Dent Grant, Frederick Dent

Grant was born on May 30, 1850, in St. Louis, Missouri. He attended West Point

Military Academy, graduating with the class of 1871. He was assigned on June

12th of that year to the Fourth United States Cavalry, spending two years on

outpost duty taking part in combats with Indians in the far west. As a result,

he was promoted to the rank of First Lieutenant and Lieutenant-Colonel by 1873,

and eventually resigned his military commission in June of 1881.

Shortly thereafter, he married Ida Honoré, the daughter of a

Chicago millionaire. They resided in New York with the widow of General Grant.

He served as republican Secretary of State for New York from 1887 to 1888. Also

during this time, Frederick served as minister to Australia, and was Police

Commissioner of New York City at the outbreak of the Spanish War, when he

became Colonel of the Fourteenth New York Volunteer Infantry, and was soon

thereafter appointed a Brigadier-General of the United States Volunteers.

During the Spanish War, he served in Puerto Rico, and

following the war, remained in command of the military district of San Juan.

Shortly thereafter, he transferred to the Philippines, commanding the Second

Brigade of the First Division of the Eighth Army Corps. While there, he took

part in the battles of Big Bend and Binacian, afterward being transferred to

the Second Brigade of the Second Division, advancing on Northern Luzon and

Zamballes.

He returned to the States in 1901 when he was appointed a

Brigadier General in the United States Army and assigned to command the

Department of Texas, with headquarters in San Antonio. In 1902, he was transferred

once again to the Philippines, to the Sixth Separate Brigade in Samar, where he

received the surrender of the last insurgent forces.

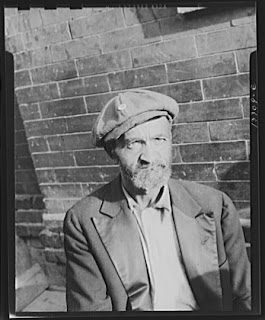

In 1914, Ida H. Grant apparently rented the house to U.S.

Senator William P. Jackson (left) and his wife, as they were listed as the

occupants in the City Directory for that year. Incidentally, another William P.

Jackson appeared in the same City Directory, and listed his profession as an

Assistant Inspector General in the United States Army, boarding at the Army and

Navy Club.

The daughter of Ida H. and Frederick Grant, Julia, was born in

the White House in 1876, while her father was fighting in the Indian Wars in

the West. Her grandfather, Ulysses Simpson Grant, was then serving his second

term as President. She grew up in Vienna where Frederick later served as the

American minister to the court of Emperor Franz Joseph.

In 1899, at the Newport, Rhode Island home of her aunt, Mrs.

Potter Palmer of Chicago, Julia Grant was married to Prince Michael Cantacuzene,

chief military adjutant to Grand Duke Nicholas, the grandson of Tsar Nicholas

I. For the following eighteen years, she lived on her husband’s vast estates

near St. Petersburg and in the Crimea until the Russian Revolution forced them

to escape to Sweden.

Princess Cantacuzene, as she preferred to be known, became the

frequent lecturer and author of three books, all relating to her life in Russia

before and during the Revolution. As a popular lecturer, she was an outspoken

foe of Communism as well as of the New Deal during the 1930s and 1940s. In

1934, she regained the American citizenship she had given up at her marriage

thirty five years earlier. She died in 1975 in the Dresden Apartment building

at 2126 Connecticut Avenue at the age of ninety-nine. Interestingly, it was designed by Albert H.

Beers in 1909, just two years before he designed the house of her mother at

1711 New Hampshire Avenue.

The son of Frederick Dent and Ida Honoré Grant, Ulysses S.

Grant III, was born on July 4, 1881 in Chicago. He too was raised primarily in

Vienna, attending the Thresianum school there before attending the Cutler

School in New York City and Columbia University in 1898. He graduated from

Westpoint Military Academy in 1903, and graduated from the U.S. Engineer’s School

in 1908. He married Edith Root, daughter of the Secretary of State Elihu Root,

the Secretary of State under Theodore Roosevelt on November 27, 1907, and

together they lived in San Francisco.

He became a D.C. resident in 1925, and lived at 2117 LeRoy Place,

N.W., when he became active in numerous urban planning affairs, including

serving as the Executive Director of the National Capitol Park and Planning

Commission. At the time of his death in 1968, he maintained a residence at 1255

New Hampshire Avenue, N.W.

The last will and testament of Ida Honoreé Grant has several

inclusions that offer insight into the lifestyle that she led while in

residence at 1711 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W. It was written on September 2,

1926, and entered into probate on September 8, 1930, shortly following her

death.

The real estate at 1711 New Hampshire Avenue was willed

exclusively to her son Ulysses S. Grant III (left) upon Ida Honore Grant’s death in

February of 1930.

Her daughter Julia Grant Cantacuzene and son Ulysses S. Grant

III were to split most of the personal artifacts and furnishings of the home,

including "all clothing and wearing apparel, jewelry and articles of

personal use and adornment, books, pictures, bric-a-brac, silver and household

furniture, articles and effects, of every kind and description, as well as any

other tangible personal property and effects, of which I may die

possessed." Ida was also proud that she was able to keep the aggregate

value of multiple bonds "intact and equal to the value of said property at

the time it was left to me, so that I might be able to make this bequest and

pass it on...to our children." The bonds in question were housed in her

safe deposit box at the American Security and Trust Company in Washington, D.C.

It was her wish that the children would be able to retain the bonds at their

face value to pass on to their children in remembrance of their father

Frederick Dent Grant.

The remainder value of the estate was to be placed in a Trust

at the American Security and Trust Company and equally dispersed over the

course of 21 years in equal parts to her son and daughter. She expressed the

trustees "to be very conservative, and to purchase only such bonds or

other securities, which, after careful investigation, they believe to be safe and

secure. I prefer that my trustees invest in such securities rather than in real

estate."

Her daughter Julia was specifically granted the sum of $50,000,

to be gleaned from the proceeds of the sale of real estate owned in the state

of Illinois. She also noted that her daughter was "amply provided for by a

trust created by my sister, Bertha Honoré Palmer, which Trust has greatly

increased in value through the able management of my brother, Adrian C.

Honoré."

To her son, she specified that "all letters and papers of

an official, business or personal character owned by me, including those which

belonged to his father, and also those which belonged to his grandfather,

General Ulysses S. Grant." She made that bequeath "in order to carry

out my late husband's express wish that his son should possess these letters

and papers."

The Nicaraguan Legation: 1931 to 1936

The residence at 1711 New Hampshire was rented by Ulysses S.

Grant III following the death of his mother Ida Honoré Grant in early 1930 to

the Government of Nicaragua for us its Legation. The Charge d’Affaires of

Nicaragua at the time, Dr. Henri De Bayle, both resided and worked at 1711 New

Hampshire Avenue, N.W., during this period.

Copyright Paul K. Williams

Fraser’s plans for the house at 1500 Rhode Island Avenue

were completed in 1879 for owners John T and Jessie Willis Brodhead, pictured

at right about 1925. It was purchased in

1882 by Gardiner Hubbard fro his daughter Mabel, who was married to Alexander

Graham Bell. In 1889, it was purchased

by Levi P. Morton, who hired architect John Russell Pope in 1912 to turn the

turreted Victorian into a classic revival house at a cost of $20,000. It remains on the site at Scott Circle in its

vastly altered form today.

Fraser’s plans for the house at 1500 Rhode Island Avenue

were completed in 1879 for owners John T and Jessie Willis Brodhead, pictured

at right about 1925. It was purchased in

1882 by Gardiner Hubbard fro his daughter Mabel, who was married to Alexander

Graham Bell. In 1889, it was purchased

by Levi P. Morton, who hired architect John Russell Pope in 1912 to turn the

turreted Victorian into a classic revival house at a cost of $20,000. It remains on the site at Scott Circle in its

vastly altered form today.