Patent Attorney and Investment Builder Chester A. Snow

A successful patent attorney, Chester Ammen Snow also

invested in building several apartment buildings in Washington, including the

Holmes and the Irving at 3014 and 3020 Dent Place in Georgetown, built in 1902

and 1903, respectfully. He was a partner in the CA Snow & Co. firm along

with Edward G. Siggers, and they maintained an office at 708 8th Street, N.W.,

adjacent to the Snow household. By 1910, the City Directory indicated that his

partner had changed to an individual by the name of Clarence A. Doyle. Their

advertisement from that year appears above.

Chester A. Snow was born in April 1844 in Virginia to

Reverend Dexter and Catherine Snow. The family moved to Washington, DC by 1880,

and lived together in a large house at 712 8th Street, N.W., by 1900. The

extended family was enumerated there that year, and included the elder Snow,

and Chester and his wife Clarissa (Parfet) Snow. She was also a native of

Virginia, having been born there in 1870.

Chester was age 50 and Clarissa age 24 when they had married

in 1894. They had one child together, Chester, Jr., in 1898, that would go on

to head the C. A. Snow Company, which was already flourishing by the time he

had been born. An announcement in the July 29, 1907 Washington Post indicated

that the wealthy couple were going to depart for a round-the-world trip in

September of that year, to include India, Japan, and Egypt. Clarissa died

sometime between 1907 and 1910, possibly on the trip itself.

According to the census taken in 1910, Chester, then age 66,

had moved into a house at 1818 Newton Street, NW, along with his niece Maud

Emory, then a widow age 42. They were taken care of by two servants and a cook.

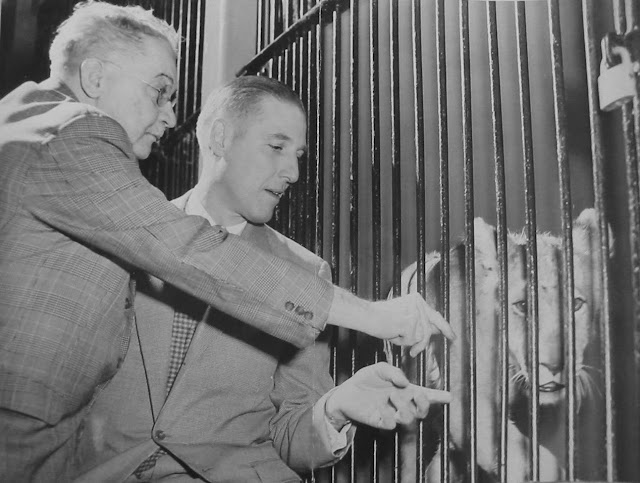

Snow was a longtime leader of the Washington Humane Society, and made the

Washington Post several times as a complainant in cases against residents using

horses that were “old and unfit to work,” or forced up snowy hills without sand

being used for traction (Washington Post, January 20, 1905).

However, Snow began courting a 36 year old resident named

Addis M. Hubard in early 1913, and the two were married on July 29th

of that year (Washington Post, July 25, 1914). They had a son named Dexter

Hubard Snow on July 25, 1914, who had been born in Europe, where Addis had

remained following their extended Honeymoon.

Their marriage lasted just three years, however, as first

reported in the January 23, 1917 issue of the Washington Post, that they had

been separated since November of 1916. Their sensational divorce trial, which revealed

an intimate relationship between Snow and his niece Maud, made headlines for

weeks throughout the ordeal, and was no doubt the subject of much gossip in the

city’s social circles. Testimony even included many love letters written

between all three parties. Custody of Dexter was the focal point of the trial.

It likely did not help matters that Chester Snow hit and injured an 18 year old

child named Harvey Magner, playing near his office on 8th Street, NW, during

the trial.

Addis claimed that their “love died on the honeymoon,” and

that she was prevented from entertaining guests in their home, denied use of their

automobile, and “never treated as a wife.” Snow countered, of course, and

alleged that their “honeymoon was spoiled because of his bride’s nervousness

and spells of hysteria.” In the end, Addis was granted custody of the child,

and both received a divorce.

The trial also shed light on the financial success of Snow,

who his second wife estimated as being worth $2 million. He also owned a farm

property coined Fenwick, near Woodside, Maryland.

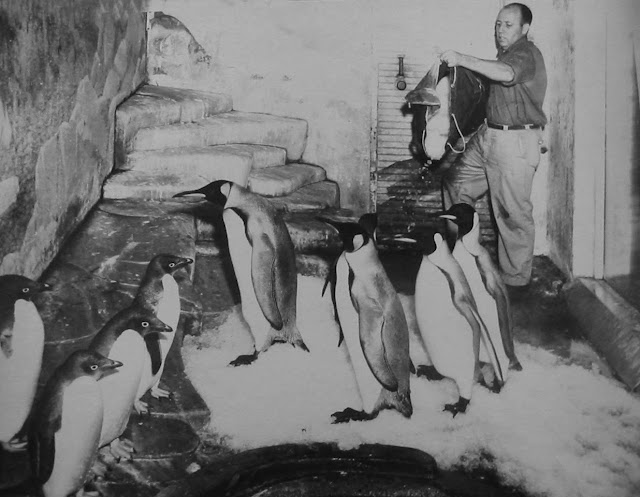

Chester A. Snow, Jr., took

over the C.A. Snow Company following an education at the University of

Pennsylvania and The George Washington University, and it became exclusively

involved in the real estate business. He had begun working there in 1916. Seen

at left, he married Enid Sims on February 19, 1923.

Chester Snow died in 1937 at the age of 93. His son by his

first wife, Chester A. Snow, Jr. died in August of 1977 in Washington, DC, and

his son by his second wife, Dexter H. Snow, died in Amherst, Virginia in May of

1996.

Copyright Paul K. Williams